Looking at the 100-plus businesses that Buffett has accumulated, a casual observer may feel that it is a collection of random businesses. But look closely and you will find a pattern. Who else, but Buffett has articulated the common thread amongst all his businesses when he published the Berkshire’s Acquisition Criteria.

A fact that we need to keep in mind is that these criteria are not for his general stock purchases but for acquiring controlling stake or whole companies, but they give a glimpse of how Buffett things about buying companies.

There are six criteria which are simple and straightforward.

1. Large purchases (at least $50 million of before-tax earnings)

Buffett looks at opportunities to deploy large amounts of cash. It makes very little sense to buy companies which would make up a fraction of a percentage or a couple of percentages in his overall portfolio. The same principle applies to investors as well – to look for companies where we can invest between 5-10% of our portfolio with conviction.

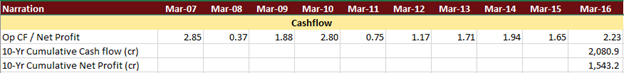

2. Demonstrated consistent earning power (future projections are of no interest to us, nor are "turnaround" situations)

Buffett looks for companies with regular and consistent cash flows and earnings. This significantly reduces his universe of investible stocks as some sectors are by their nature not amenable to such characteristics. Cyclicals like cement, metals, sugar, oil have never been part of Buffett’s core holdings -though he has had shorter term (five years) positions in stocks like PetroChina.

"Both our operating and investment experience cause us to conclude that turnarounds seldom turn," Buffett wrote in 1979, "and that the same energies and talent are much better employed in a good business purchased at a fair price than in a poor business purchased at a bargain price."

Investors should focus on finding good businesses with reasonably consistent cashflow and ability to generate profits for a prolonged period (many years or decades) and then try to buy them at a discount to intrinsic value.

Having a portfolio of good businesses, without being leveraged and not needing to pull out of the market when there is a downturn, can produce good results over a long period of time.

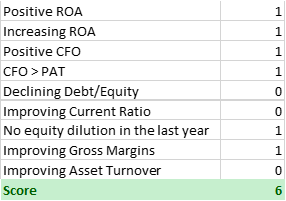

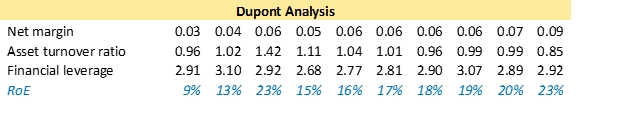

3. Businesses earning good returns on equity while employing little or no debt

Stocks of highly leveraged companies should come with a statutory warning like in cigarette packs, “Investing in highly debt-ridden companies is injurious to wealth”! The foremost reason for problems in companies over a long period of time, which results in permanent loss of capital for investors, is high debt. If an investor can simply avoid them, half the battle is won.

Return on equity (ROE) is one of the most important ratios to look at for a company. A business needs to be able to generate ROE above its cost of capital and above an investors opportunity cost to be considered for investment. Over a long period, a business which generates high ROE will tend to be value accretive.

4. Management in place (we can't supply it)

An honest and competent management that treats minority shareholders as equal partners in the business is crucial for the long-term success of an investment. Since, minority shareholders usually are not able to control or influence management decisions and policies, special emphasis is required to understand that the management would not try to enrich itself at their expense or try to get into ‘diworsifications’ for self-aggrandizement.

5. Simple businesses (if there's lots of technology, we won't understand it)

Here again the focus is on businesses which can be understood by the investor – the circle of competence. Understanding means that the investor understands the industry dynamics, the competitive positioning of the company within the industry, how the company makes money, the demand and supply economics etc. It also means some idea about how the long-term future would look like for the business. This is precisely why Buffett tends to avoid those industries and companies which are prone to rapid disruption and change and sticks to the old-world businesses.

An investor can start with studying businesses that they are familiar with and learn more about it and its competitors. Over a period, the circle of competence can be expanded to include new industries and companies by continuous learning.

6. An offering price (we don't want to waste our time or that of the seller by talking, even preliminarily, about a transaction when price is unknown)

Price is the most ready-made data that is always available for listed stocks. Every day Mr. Market gives a quote that an investor can either take or let pass. This criterion, if strictly interpreted, is not for investors, but can be expanded to incorporate the most critical concept of “margin-of-safety”. An investor should only look to buy a business if the quoted price is below the intrinsic worth of the stock. It also protects an investor from mistakes and market downturns.

Since last year the Q&A session at the Berkshire Annual Meeting has been webcast live giving an opportunity for investors across the world an opportunity to watch the Buffett-Munger duo in action, answering questions across various topics. Every year, there is some nuggets of wisdom that can be learnt from these sessions and this year was no different.

Munger and Buffett have spent their entire lives by sticking to their investment principles not chasing fads. “A lot of people are trying to be brilliant, and we are just trying to stay rational”, said Munger. Buying and holding great businesses over very long periods of time has been extremely rewarding. As Buffett aptly put, "We did not buy American Express or Wells Fargo or United Airlines or Coca-Cola with the idea that they would never have problems or they would never have competition. But we did buy them because we thought they had very, very strong brands”. Brands of course allow Buffett to invest in companies where he can predict consumer behavior in the long term.

Over the years, Buffett has been sector-agnostic and bought wherever and whenever he has seen value.

"Charlie and I really do not discuss sectors much, we're really opportunistic. We're looking at all kinds of businesses all the time. We're hoping, we get a call, and we know in the first five minutes whether a deal has a reasonable chance of happening… We don't really say we'll go after companies in this field or that field”, Buffett said.

Markets are at time irrational and provides good companies at cheap valuations. That is the time when margin of safety in stocks are high and investors need to take advantage of. As Buffett mentioned, "It is the nature of market systems to occasionally go haywire in one direction or another."

The world is seeing a plethora of new technologies resulting in completely new businesses. In the coming years, some existing businesses will die and others will take their places. Buffett mentioned that artificial intelligence would result in significantly less employment in certain areas, but that’s good for society, though it may not be good for a given business. As an example of such widespread disruption and its impact on businesses, Buffett said, “Autonomous vehicles, widespread, would hurt us if they spread to trucks, and they would hurt our auto insurance business. They may be a long way off. That will depend on experience in the first early months of the introduction. If they make the world safer, it will be a very good thing but it won't be a good thing for auto insurers."

If we follow the basic rules laid down by Buffett, keep learning continuously and apply common sense to investing the long-term outcome is likely to be positive.